- Home

- D J Brazier

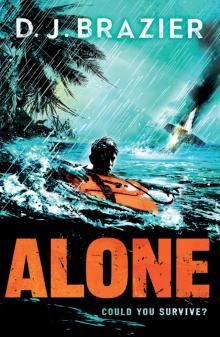

Alone Page 13

Alone Read online

Page 13

I turn and run back to camp. I have to find Galaxy. To make sure he’s safe. I spot him almost immediately, fast asleep on top of the log pile, seemingly unconcerned by the storm’s approach. Not wanting to alarm him, I gently lift and carry him to the base of the Joshua Tree. At least we’ll have some shelter here. Galaxy yawns and stretches his rear legs but doesn’t bother to open his eyes. I settle down beneath the tree’s dense awning with my back against the trunk and Galaxy’s warm body curled in my lap. And in silence I wait for the storm.

Moments later the first clouds arrive, dumping rain and hurling bolts of lightning. My ears pop as rain pelts the trees and the wind howls through the canopy, stripping leaves and snapping branches. A great boom of thunder shakes the sky and I feel its shock wave hurtle down the Joshua Tree’s trunk and rattle my spine.

Galaxy’s eyes burst open and he stares up at the raging sky. I hold him firmly, with one hand tickling his chin while I stroke his back with the other, and I try to tell him there’s nothing to be scared of, but my words are torn away by the wind, and Galaxy wriggles out of my grasp and gallops out into the full force of the storm. I yell at him to come back, terrified he’ll bolt into the river and head for his holt. But he doesn’t. He crouches in the open instead, coiled and tense, and when the next flash of lightning comes he barks with glee and bounds to the log pile and tries to reach the top before the thunder cracks. The storm is directly overhead now and the thunder arrives no more than a second or two after the lightning, but Galaxy is so fast he makes it to the top in time and stands on his wooden summit barking at the sky, and snapping at leaves flying past his head. Then he leaps off and crouches a little further away this time, and waits for the next bolt of lightning. It’s plain to see he’s not afraid. Far from it. He’s bursting with excitement. He’s fearless. Mad! And his exhilaration is irresistible.

I stand and run out to join him and immediately slip and land face down in the mud. Galaxy whistles and runs to me, butts my forehead and nibbles my hair then runs away. I laugh, and try to chase him around the log pile, but with his clawed and webbed feet it’s no contest, and he laps me as I spend more time spread-eagled in the mud than vertical, and even when I do manage to stand the wind threatens to knock me down again. The rain hits hard and fast, BB-gun hard, and each crack of thunder vibrates my bones and tissue. I can’t tell whether it’s water or blood pouring from my ears.

This is absurd. Insane! What if I get struck by lightning? Or a falling branch whacks me on the head? Or I slip and break a leg. Or I get swept into the river? I should be terrified. I should be cowering in the shelter of the Joshua Tree. But I’m not. I’m dancing in the eye of the storm and I’ve never felt so invincible. So alive!

I kick my bedding into the air and dance around the fire; I manage two moves before my feet skate from under me and my arse smacks into the mud. Galaxy leaps from the log pile onto my chest, and I shriek with laughter and grab him in a bear hug. We wrestle and roll across the mud, and I hardly notice his fish breath and rasping tongue as he licks my face and yaps. I roll him off my chest and he runs to the other side of the log pile and hides. I don’t even bother trying to get to my feet, just scramble after him on all fours.

For the next hour or so while the storm shakes the trees, and pounds the earth and tears the sky, we wrestle and splash and slide, and chase whirling sticks and flying flowers, and each other, and screech with joy until dusk comes and it’s too dark to play any more.

I collapse beneath the Joshua Tree. The rain is still falling but the wind has died down and thankfully my seat amongst the tree’s roots is above the pooling water. I’m knackered, and soaked to the bone, and bruised all over. But I’m grinning, and glowing inside as well. The storm is fading, and soon it will end, they always do, and when it does I will still be here, and so will Galaxy.

Sometime during the night, when the rainwater snaking down the Joshua Tree and dribbling down my back has made sleep, or even sitting down in comfort, impossible, the last traces of warmth and defiance drain out of me. I so want to sleep, and dream myself into a hot bath, with a soft towel and dry clothes. I want the rain to stop. I want the sun to rise. To feel its warmth. I want this sick feeling to go away. I want this nasty little voice in my head to be quiet. The one that keeps reminding me about what I said I’d do today. The one telling me that when dawn comes I have to go. I have to leave Galaxy. Telling me I have a promise to keep.

THIRTY-FIVE

Sunrise.

At last.

The sky is no longer black. But my mood is. It’s still raining. My legs are stiff and sore, my bum hurts and my body is covered in bruises. The fun of last night’s rain dance seems a long time ago.

My camp site has been destroyed. My bed’s been blown away and all that’s left of the fire is a soggy mess buried beneath mounds of leaves and fallen branches. Muddy puddles are everywhere, and the mosquitoes are loving it.

Squelching barefoot through puddles, I take a winding route to the toilet area, head down, trying to spot hidden thorns and splintered branches. I should put my trainers on, or take my time and tread more carefully, but I’m too crabby and in need of the toilet to turn back now.

Rounding the bend I wipe the rain from my eyes and blink and stare at a landscape transformed. The stream has broken its banks and flooded the sandspit. At least two thirds are now under water. Snail Rock is completely submerged. The swollen river is dark brown, flowing fast, and spilling over the lip of the riverbank. A large chunk of the bank opposite has collapsed and only the tip of Otter Rock remains above water, wrapped in weed banners streaming in the current.

I’m stunned, gutted. There’s no way I can fish in that torrent, let alone launch a raft, it would be torn apart in seconds. The raft! One glance is all it takes to confirm that the spot where I left my carefully chosen timber is now under at least a metre of water. I take a deep breath and slowly clench and unclench my fists. I need to get my head together, to calm down. The rain will stop and the water will recede. I can collect more wood. I can build another raft and I can catch more fish. As long as I still have my fishing rod…

With a sense of dread knotting my stomach I hurry back to camp, and gaze up at the bare branches of the Joshua Tree. My fishing rod is gone. So is the life jacket. Dropping to my knees I frantically search through the soggy muck, digging under leaves and broken boughs, and I find my trainers first, then my life jacket, buried beneath the refuse from last night’s feast, smeared with sticky mango pulp. I quickly check the pockets. Dad’s watch is still there. So is the fire glass, and it’s still in one piece. Relief washes over me. Now if I can just find the fishing rod I’ll be fine.

Squinting through the rain I scan around, trying to determine if any of the sticks nearby have the distinctive bare patch where my palms rubbed the bark away on my fishing rod. But I can’t see it anywhere. I grab my trainers and sit on a log and pull one on. I’m staring at the river and trying to estimate how far the wind may have carried my rod as I pull on the second trainer, when I feel an agonising stab in the sole of my foot. Yelping with pain I yank off my trainer, and scrape away a layer of sandy mud to reveal a small puncture wound near the base of my big toe. The hole is too small to bleed but a red blotch has appeared around it and it’s starting to burn. I pick up my trainer and shake it, and a small black object falls out, bounces off the log and lands on the ground by my feet. It scurries away. A scorpion! I fling my trainer at it, and miss, then hop back to the swollen stream to bathe my foot. The running water soothes and numbs my toe and I keep my foot submerged until the wound feels no worse than a sand-fly bite.

Splattering a mosquito tapping a raised vein on my forehead, I grind my teeth and take half a dozen deep breaths to try to calm myself. My mood has not improved since waking, if anything it’s a thousand times worse. Today began badly and it hasn’t got any better. I want to wind the clock back, to start the day again. Or better still, I want to relive yesterday on a loop instead. With head down an

d eyes scanning the debris, I heel-walk back to camp, on the lookout for thorns and more scorpions. Rustling sounds come from camp. Galaxy’s back. Good. I could do with cheering up, and with the river so high and fast I won’t be leaving today after all. Perhaps my luck has changed and he’s caught me a fat piranha for breakfast. Or more likely he’s brought me a slimy catfish instead. I’ll find out soon enough.

I raise my head. And see the pig. Stocky and wide, its hairy black back and soiled buttocks are facing me and swaying as it rakes the ground with its front trotters.

A litter of seven or eight brown and white striped piglets are racing around it, playfully nipping at each other and trying to latch onto the saggy teats hanging from the sow’s belly. As I stand stunned and motionless, the pig lunges forward and lifts its head with my life jacket snagged on its tusks, then shakes its head. I can see pieces of Dad’s watch fly through the air. The life jacket slides off the pig’s tusks and she snorts and scoops up a small round object, and in the same instant that I realise what it is, the pig tosses its head back and I hear a distinct crunch followed by slobbering sounds as my fire glass disappears down its throat. Then the pig grunts, lowers its snout, and turns its attention to the rest of Dad’s watch.

A red mist descends. I scream and run towards the pig and draw my leg back to kick it as hard as I can. But as I do so I skid and lose my balance and my foot catches one of the piglets instead. The piglet squeals and tumbles into a muddy puddle and the rest scatter, squealing in fear. I fall hard, winding myself, and my thigh slams into the edge of a concealed log which gives me a paralysing dead leg. The sow snorts angrily but to my surprise she doesn’t run away. Instead she nudges her piglet out of the puddle and turns to face me, eyes blazing and trotters pawing the earth.

I’m in serious trouble.

The sow is in crazed-mother-protection mode and I’m unarmed. With my dead leg I can’t even stand, let alone run. I desperately search around for some sort of weapon. Before I can find anything, the pig charges, emitting a hideous, hostile cry. I manage to curl up in a ball with my arms wrapped around my head just in time, as her tusks graze my forearms, drawing blood.

The piglets are squealing hysterically now and running around in blind panic, fuelling the sow’s rage, and she gouges me again and again, lacerating my arms. I try to get up. But I can’t. My leg won’t take my weight. So I stay curled up in a ball and play dead. But the pig rakes my legs with her trotters and I have a terrible feeling that she’s not going to stop until I’m fatally wounded, or dead.

Then I hear a whine, long and shrill, and through a gap between my arms I see a blur of brown. Galaxy leaps onto the pig’s back and sinks his teeth into her shoulder. The sow bawls and twists her head, trying to reach him. But Galaxy holds on with his claws hooked in the sow’s hide as she runs and spins in circles. Then she rears and bucks, throwing Galaxy off, and he twists in the air, landing on his feet between the pig and me. He spins to face her, back arched and fur bristling, ears pressed flat against his head, teeth bared. A continuous high-pitched wail is pouring from his mouth. Galaxy’s less than half the pig’s size and a third of her weight yet he’s warning her to stay away. To leave me alone. But the pig is too enraged to heed the warning and she charges again.

Galaxy holds his ground. Then at the last moment, just as the pig is upon him, he jumps vertically, like a coiled spring suddenly released. But the pig rears as Galaxy leaps, and he’s not quite high enough to clear her thrusting tusks. One slams into his stomach while the other catches him full in the face, entering his mouth and ripping through his cheek. Galaxy’s body crumples in mid-air and he slumps to the ground and lies in a heap. Not moving.

The pig glares down at Galaxy, and starts to trample him. She clamps her mouth around his head. Something explodes in my brain. A blinding eruption of rage and hate that ignites every nerve and fibre in my body. I lurch forward, dragging my dead leg, and I punch the pig as hard as I can in the side of her head, over and over, until I’m sure my wrist is broken, and I can punch no more. But I’ve landed enough blows to stun the pig and make her release Galaxy, and I claw at her face, and jam two fingers into her nostrils and force my thumbs into her eyes. The sow yelps and jerks her head and I bite her neck and try to tear her throat out. But her hide is too thick and my jaws are too weak, and I gag on the mouthful of bristly hair and have to let go. I jump on her instead. Her legs buckle and she topples onto her side, thrashing trotters hammering my kneecaps. Grabbing her ears I push her face down into the puddle, and use all my weight to force her snout beneath the surface. I can feel her heart thumping hard and fast against my chest and it takes all my strength to keep her head beneath the surface, but I’m too consumed with hate to let go. Then the bubbles from her mouth die to a trickle and her heartbeat slows. I just have to hold on for a few moments more and it will be over. And then I hear it; the pitiful cry of pain and loss Galaxy makes when he dreams of his absent mother. I lift my head, and stare at his crumpled form. But Galaxy hasn’t moved, and he hasn’t made the sound. One of the piglets has.

The piglet is standing at the edge of the puddle, so close to me I can see a white crescent-shaped scar on his pink snout and raindrops clinging to his eyelashes. I growl at him and he runs, but after a few skittering paces he turns and walks back, stamps the water and cries again, the same pleading cry of distress and fear as before. I feel his mother’s heart thump hard beneath me, and tiny bubbles stream from her mouth, and with her last pulse of life she tries to break my grip and rise, to defend her young.

I look at the piglet, then Galaxy, and with a howl I slide off the sow and drag her head from the water. As soon as her snout hits the air the sow shudders and retches, and muddy water and snot stream from her nostrils.

Crouching on all fours over Galaxy’s body, I glare at the pig and snarl. My blood is still boiling. If the sow makes one move in our direction I will kill her. No question. No second chance.

All eight piglets crowd around their mother, butting her face and urging her to stand. After a few faltering attempts she does so, and looks blearily in my direction. I can tell by her glazed eyes and drooped head that the fight’s been knocked out of her. The piglets are clamouring for attention now and the sow lowers her head, sniffing and licking each mucky face in turn, as if counting them, before turning and trotting away, tail swishing, her piglets swarming around her, squealing impatiently and climbing over each other to reach her swaying teats.

I turn my attention to Galaxy. Lying on his side, he’s breathing hard, eyes closed and mouth open. Pig drool covers his face and blood oozes from the hole where the tusk pierced his cheek. Slivers of white bone are visible in the wound and it’s clear his cheekbone is broken. The skin appears to be intact on his stomach but I have no way of telling how badly injured his insides may be.

As I dip my trembling hands in the puddle and carefully wash the muck from his face, Galaxy opens one eye and chirps, and weakly paws at the ground, trying to stand. I place my palm firmly on his side, making a shushing sound, and sit beside him, then gently lift him to my chest. In a stuttering voice I start to tell him off for being so stupid as to attack the pig. As I speak he never stops chirruping with affection, his eyes never leave mine, and he stretches his head up towards my face. I lift him a little higher and he nuzzles my neck, and even though he is clearly in great pain he licks my hand, wincing as he does so. My heart feels like it’s being ripped in two and I’m close to breaking, but I know I have to keep it together. I have to be strong, for both of us.

Then Galaxy does something he’s never done before. He lifts his paw and tenderly strokes my cheek, like I would do to him, as if to reassure me that everything is OK. Then he lowers his front leg and places his paw in my palm and sighs. I stare down at his tiny paw clasped in my hand and his liquid-brown eyes gazing up at me, full not just with pain, but with trust and friendship as well, and the tears come. And I can’t stop them. My shoulders shake and sobs rack my body, and I hold Galaxy a

s tightly as I dare and bury my face in his fur. Galaxy grunts in puzzlement and laps at the salty tears dripping from my chin, and makes his Give me more! cry, and his demand is so unexpected that I laugh, and my croaky laughter eases the choking pain lodged in my chest.

Galaxy chirps in response and I gently squeeze his paw, and kiss his muddy forehead. I have no way of knowing how serious his wounds are, and I have no idea how to heal him. All I know is that he risked his life to save mine and now I have to find a way to save his. As long as he lives, I will never leave him.

THIRTY-SIX

The blossom floats for no more than a second or two before the raindrops pummel it under and it sinks to join the countless others I’ve tossed in the puddle since yesterday. The endless, monotonous rain continues to fall. It’s been three days now since the storm, as if a switch has been flicked from ‘Dry’ to ‘Wet’ and the monsoon season has begun.

With 99% of the sandspit now under water we’re confined to a small patch of mud and puddles around the base of the Joshua Tree, and even this is shrinking by the hour. It’s only a matter of time before the river claims this last scrap of solid ground. At the rate the rain is falling that could be hours rather than days away.

There’s no escaping the rain. No shelter beneath the leafless trees. No way to get warm or to keep Galaxy’s wound dry, and I don’t know if I should anyway. Galaxy is asleep in my lap, tongue lolling, and even with the cold rain saturating his fur, his body is hot to the touch, his breathing fast and uneven. It’s clear he has a fever and the bulging lump on his cheek tells me his wound is badly infected too.

Alone

Alone