- Home

- D J Brazier

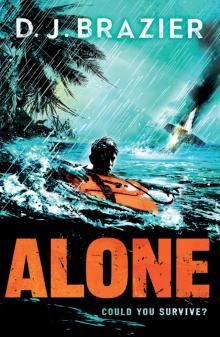

Alone

Alone Read online

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Part Two

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Part Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Acknowledgements

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781448188413

Version 1.0

First published in 2016 by

Andersen Press Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London SW1V 2SA

www.andersenpress.co.uk

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

The right of D. J. Brazier to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Text copyright © D. J. Brazier, 2016

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available.

ISBN 978 1 78344 403 8

For Mum

PART ONE

ONE

I’m being boiled alive.

Waves of searing heat roll over me. I turn my head and heave, spewing up hot water thick with aviation fuel. It burns my already scorched throat.

Something explodes on the other side of the plane and I try to duck but the life jacket keeps me vertical and I can’t dip my head below the surface. Another explosion, the biggest yet, ignites the fuel slick and a ring of flame encircles me, so close it blinds me. I dig my fingers into the life jacket and scream, ‘Dad!’ again and again. There’s no reply, just the roar of the flames. A finger of fire jabs my cheek, blistering the skin. I can hardly breathe in the thick smoke and I can smell my hair singeing. I have to get away. But I don’t know how. My head is pounding and I can’t think clearly. There’s too much noise, too much smoke, heat and confusion.

I can’t swim through the flames. I’ll have to try to dive beneath them. And I have to do it now.

I take the life jacket off. Without its buoyancy to support me, the weight of my heavy jeans and trainers pulls me under and I swallow more water. I claw my way back to the surface, throw the life jacket through the flames, take a deep breath and dive. I swim as hard as I can, kicking my legs, desperately trying to clear the fire above. The water is pitch black and I have no idea how wide the flaming wall is but I keep going as long as I can, heading away from the heat and noise until it feels like my lungs are about to burst and I can stay under no longer. I break the surface, coughing and retching. The flames and smoke are behind me. Ahead is just blackness and bullets of silver rain. Something soft bumps against me – the life jacket, smouldering and half-submerged. I grab it and pull it on, and as I do so a piece of material floats free. In the flickering light from the flames something familiar about the fabric’s colouring and pattern catches my eye and I scoop it up before it drifts out of reach. Holding it close to my stinging eyes, I squint at the checked material and immediately recognise it. It’s the ripped chest pocket of a shirt. Dad’s shirt.

Another explosion behind me. Something slams into the back of my head, and everything goes black.

TWO

I wake slowly, drifting back to consciousness. My head is throbbing and it takes me a moment or two to realise I’m lying on a beach with my blistered cheek pressed into hot sand and my arm twisted painfully beneath me. At first I have no idea where I am or how I got here, but then memories of the plane crash come flooding back – the storm, the screaming engines. The fire. Dad’s shirt pocket.

Dad!

The sun’s glare blinds me as I rise unsteadily to my feet and yell, ‘Dad! Dad!’ and, ‘Help! Please. Somebody help me,’ over and over again until it’s too painful to yell any more.

I hesitantly probe a painful lump on the back of my head, matted with dried blood and hair, then shield my eyes and look around me. The sandspit I’ve washed up on slopes down to a fast-flowing river, wide and brown. Behind me the jungle is dark and dense, and unbelievably loud with the cries of birds and other creatures.

The inside of my mouth feels like I’ve been chewing sandpaper and I have a raging thirst. I take off my life jacket and walk to the river’s edge, swerving to avoid stepping on an eyeless fish crawling with ants and flies. The water is lukewarm and murky in my cupped hands, but after a moment’s hesitation I take a sip. It tastes stale, and flat, like a fizzy drink left in the sun. But at least it’s wet, and partially soothes my burnt throat, so I sink my face in the river and gulp until I can stand the taste no longer.

The last decent drink I had was a Coke at the airport, guzzled down while Dad called Mum to tell her we were on our way home. I can see him clearly in my mind, phone in one hand and a packet of crisps in the other, chuckling as he teased Mum about the state of the Single Prop plane we were about to board. The plane to take us on the last leg of our journey back to the main airport. Then in two days we’d be home.

My shoulders slump. I turn and walk to the shade of a tree and sit down with my back against the trunk. Hugging my knees to my chest, I squeeze my eyes shut and try to work out how in hell I got here.

‘The trip of a lifetime.’ That’s what it was supposed to be. Paid for with the money Gran left me. Money she made me promise to spend on a great adventure, and not just ‘fritter away’. She’d been saving for years in preparation for the day when she and Grandpa could go on their own dream trip.

But life kept getting in the way, she said. Then she got ill. Then she died. But before she got too sick she put all the money in a bank account and made me promise I’d make the trip for her, and see the world, especially the jungle, and do it now, before it was too late. With one condition – Dad had to come.

Dad didn’t want to. ‘Things aren’t good at work, Sam,’ he said. ‘I can’t afford to take the time off.’ His usual excuse. But I p

leaded and pestered, wearing him down, and I even played the ‘But we never do anything together’ card, and I could tell he was wavering. Then Mum helped, after I’d worn her down too. ‘It’s what your mum wanted,’ she told him, and she said it would be good for Dad and me to spend some father and son time together, and who knows, he might even enjoy it. Dad laughed and said Mum just wanted some peace and quiet on her own, but I could tell he knew Mum was right.

And this trip with Dad has been brilliant. Even better than I hoped. We’ve seen and done some amazing things and I’ve never seen him laugh so much as he has in the past three weeks. At times I’ve hardly recognised him. Having him all to myself has been incredible. There’s been time to talk. About anything and everything. About things we’ve never spoken about before. About how I can’t talk to girls. How badly I sometimes want a brother or sister, or better still a dog, and how I hate being shorter than all my friends. And even though I’m not sure he really understood, he listened, properly for once, and that’s enough. Then he told me things too; about his life before I came along. About how much he hates his job sometimes, and that’s why he’s so hard on me about doing my homework and not ‘wasting my life’ on Minecraft. He talked about what happened when he first met Mum – how shy he was, and how long it took him to find the courage to say hello to her, then to ask her out. Then he said, ‘Lucky for you I didn’t give up, eh?’ and grossed me out.

A loud screech comes from the undergrowth, and I jump to my feet and spin round but I can’t see anything in the dense foliage.

Still thinking about Dad, I walk to the top end of the sandspit, past a crooked tree overhanging the water, and peer upriver for any sign of the plane. But I can only see a little way upstream, to a bend in the river, and with a sinking feeling I realise I have no idea how far I drifted from the plane after I blacked out.

Sweat drips from my brow and I can feel my arms burning in the hot sun, but thankfully there’s a stream here, winding out from the jungle, and the water tastes clean and far fresher than the river. So I drink until my stomach’s full and sit in the shade, rocking gently back and forth, trying to figure out what to do.

I could go looking for the plane.

No. Stupid idea!

It could be miles away, and before the trip began Dad made me promise that if we ever got separated I was to stay where I was, and he would find me, however long it took. And he will. I know he will. Dad doesn’t make many promises, but when he does, he keeps them. I just have to wait.

Something tickles my neck. A small brown ant. It scurries down my arm and halts at my elbow, feelers waving. I try to gently brush it off without killing it, but as soon as my hand touches the ant it bites me. Tiny needle jaws pinch my skin, and I yelp, more in surprise than pain, trying to flick it away. But it clings on, and is quickly joined by dozens more. I jump to my feet and thrash my arm up and down, trying to shake them off, but they just tighten their grip and hang on. Glancing at the tree I’ve been leaning against I see a long column of ants streaming down the trunk and out onto the sand towards the dead fish. I’ve put myself between the ants and their meal and they’re not happy. More swarm inside my T-shirt and nip my chest and I tear it off and run down to the river, wading in and dunking my head under the water.

I sit in the shallows for ten minutes or so, reluctant to leave the cool water, until I feel the skin on the back of my neck burning and begin to think about what sort of creatures could be lurking in the dark waters. Something calls close by, a sort of barking sound, followed by a big splash. I leave the river.

Walking the other way along the sandspit, I slump down in the shade beneath the tallest tree I can find — a giant which towers over the others.

Hours pass. I call for Dad and for help repeatedly, but with no reply. The sun climbs higher, the air gets hotter and more humid, and each trip to the stream for a drink leaves me drenched in sweat. I sit and scratch at the ant bites itching on my arm, or tug at my tangled hair, and hope Dad is close by.

By mid-afternoon I’m bored and starving and I can’t sit still any longer. I have to do something. Search for food, bathe my blistered arms, or make a HELP sign out of driftwood perhaps. No. The sun is still too hot.

Then I jump to my feet. I’ve had a brilliant idea! I’ll climb a tree and find out where I am. With any luck I’ll be able to spot the plane close by, or a village, or a boat. Climbing I can do, it’s one of the few things I’m good at. Excited by the thought of rescue, I grab a thick vine entwined around the giant tree’s trunk and make a start, not bothering with the long, hot walk for a drink first.

The tree isn’t hard to climb. Thick vines provide plenty of hand- and footholds and I make good progress to begin with. But after half an hour or so, the vines end and branches from neighbouring trees intertwine to create a dense barrier. I have to force my way between them, sometimes leaning right out into space, telling myself not to look down, and hoping the next branch or vine I reach for doesn’t snap in my hand.

After another hour of twisting and wriggling, I’m exhausted, dripping in sweat and unbearably thirsty. The climb is far harder and more demanding than I expected and I reckon it will take me another two or three hours at least to fight my way through the rest of the canopy stretching high above. I slump back against the trunk and tear twigs from my hair. My brilliant idea has backfired. I’m worn out, dizzy and higher than I’ve ever been before. It would be beyond stupid to try climbing any further. Unless I head back now I may not make it down before nightfall.

I pluck a leaf from my clammy brow and as I do so I notice a mass of flowers directly above me, snow white and dotted with yellow spots like miniature suns, and hearts of stunning scarlet. They are the most beautiful flowers I have ever seen and I know what they are. Orchids. Mum’s favourite! Dad always buys them for her birthday and she has them all over the house. But these orchids are much bigger than any I’ve seen before, and far more impressive than anything stuck in a pot. And best of all, where the leaves meet at the stems’ base they form a cup, full of rainwater.

I tilt the plant towards me and greedily slurp the water, after picking out a couple of drowning bugs first. I don’t know what else is in the water but as I gulp it down it’s like drinking one of those energy drinks my mates sometimes share but Mum won’t buy me. Well, whatever is in the water works, and the energy boost is more than enough to convince me to keep climbing. I reach for the branch the orchids are growing on, and pull myself up.

Finally my head breaks through the canopy and my eyes snap shut. After so long in semi-darkness the dazzling brightness of the sun bores into my skull. Eager as I am to take a look around, I have to wait until the dancing dots fade from my eyelids before I dare open my eyes.

My heart drops. The jungle stretches as far as I can see in every direction, immense and never-ending. Nothing breaks the carpet of green. Nothing but the river below me, which I can now see is no more than a skinny worm in comparison to the giant brown snake it flows into – the Amazon. There’s no sign of the plane. Or a village or town. No buildings. No smoke curling up from the trees. No boats. Nothing.

I cup my hands and yell, ‘Dad!’ and, ‘Help!’ a dozen times but all I get in reply is screeching birds taking flight, and monkeys howling at the sound of my shrill voice. I am alone.

THREE

The night seems endless. Sleep is impossible. The nightmares are bad enough, reliving the crash and waking screaming and shivering with fear. But the dreams are worse. At least, waking from them is. The slow, painful realisation that I’m not in bed at home and it isn’t the television I can hear.

I try lying down but the ground is too hard and uneven, and insects swarm all over me. So I sit upright, arms clasped around my knees, trembling and tense, dreading the next rustle in the undergrowth, or harsh scream signalling the death of another poor creature.

The jungle is black, loud and menacing, and I have no way of telling what may be crouched within the foliage, watching me, impatiently

waiting for me to fall asleep, drooling with hunger at the scent of my sweaty body. But a few terrifying possibilities come to mind. My teacher says I’m lucky to have such a vivid imagination, but I don’t feel lucky now.

I rub my cold legs, and try to convince myself there are no monsters lurking in the darkness. But I can’t. The dark is too thick and sinister, too threatening. This isn’t the soft dark that fills my room when I’m warm and comfortable beneath my duvet. This dark is solid. Impenetrable.

The night drags on. Hordes of insects crawl all over me. In the black jungle creatures howl and fight and kill and feed. I am more tired than I have ever been, but I’m too cold and frightened to sleep and I can’t rest knowing there is no other human being for miles around. Perhaps even hundreds or thousands of miles in every direction.

I have never felt so lonely.

Some sort of beetle crash-lands in my hair and I scream. I jump to my feet and rake it out, vigorously rubbing my numb arms and legs. This is torture. I so badly want to be in my bed right now, with my duvet and soft pillow and the muffled sounds of the television downstairs. I want something to eat. I want Dad to find me. I want Mum. But more than anything, I want it to be light again.

Finally dawn comes. Black fades to grey and the horizon pales to the colour of weak orange squash. Birds sing in the trees and fog blankets the river. After a short while the fog clears and the sun shines through, bringing warmth and light.

And mosquitoes.

At first they appear in ones and twos, jigging in front of my eyes, as if sizing me up. I clap my hands and splat two in quick succession. But loads more arrive and land on my exposed skin. I slap angrily at the ones feasting on my sunburnt neck but there are too many of them and the itching becomes unbearable. So I run. I run along the sandspit, flailing my arms above my head and the mosquitoes follow me, hovering, taunting me with their whiny laughter and dropping back down to bite me as soon as I lower my arms.

But the sun is already too hot and I am too tired to run in the soft sand for long. I wade into the river and sit down instead, submerged up to my eyes with my T-shirt draped over my head while I try to figure out what to do.

Alone

Alone