- Home

- D J Brazier

Alone Page 10

Alone Read online

Page 10

TWENTY-TWO

Dusk. I shiver and wrap my arms around my chest. As soon as the sun sets the temperature will plummet and my T-shirt will provide little protection from the cold. Worse still, nightfall will trigger the emergence of the jungle’s nocturnal predators and with no spear or fire to deter them, I’m easy prey.

It doesn’t take long for the torment to begin. Midges find me first. Hordes of them. They’re so small I can’t see them in the dull light but I can feel them biting every exposed inch of skin on my head and arms; feasting in silence and leaving a maddening itch.

I plaster mud over my arms and face and rake my muddy fingers through my hair to protect my scalp, like I did in the mud bath, but the midges are even more determined and persistent than the mosquitoes were and a few still manage to find the parts I can’t protect; the tiny strips of skin between my eyelashes, and inside my nostrils. My lips and inner ears.

Within minutes my ears feel like they’re on fire and I want to slap and pinch them hard, and scream abuse at the midges. But I’m afraid that if I open my mouth the midges will feast on my lips and tongue and I daren’t risk alerting any animals nearby. So I grit my teeth and try to roll my lips into my mouth instead, and dig out another handful of mud to coat my ears with. And as I do so I feel something hard and sharp digging into my left thigh.

Keeping my right hand free to swipe at the midges I force my left hand deep into the mud until my fingertips touch the solid object and I can grab it and twist it to and fro, until eventually it comes loose and I manage to work it up the back of my leg to the surface. Holding it close to my face I can see it’s a bone. A big one. As long as my forearm, with a splintered end and a ball joint at the other. Probably an animal’s leg bone. The remains of some previous victim. I grip the bone hard. It’s useless against the midges but its solidness and weight are comforting. At least now I have a weapon.

That night is the worst I have ever known. And the longest. I’m so cold my teeth chatter uncontrollably and my jaw aches, and all I can think about is how I’m going to die. Not if. Or when. Just how. No moonlight penetrates the cloud-filled sky and in my tormented imagination every rustle and crack from the darkness signals the presence of a skulking creature impatiently watching me, waiting for me to fall asleep before it attacks. Perhaps my executioner will be a jaguar that picks up my scent and crushes my skull in its jaws, like a soft-boiled egg in an eggshell. Or a pack of wild pigs will find me and gore me to death. Or a snake or spider will strike, silent and unseen, and retreat to the blackness to wait and watch while I die a slow and agonising death.

Another rustle in the darkness, and the panic swells in my chest as the feeling of being watched intensifies. I can sense something, I’m sure of it; a bloodthirsty presence, lurking in the undergrowth. I’m getting hysterical now, I know I am, but I can’t help it, and I can stay silent no longer. I pound the ground with my bone club and scream at the darkness, ‘No! Go away. Whatever you are, go away!’ It’s not fair. I’ve done nothing to deserve this!

The jungle falls silent for a while, but then the rustling resumes, sporadic and terrifying. I wet myself.

I can’t take this. I have to do something, anything to stem the terror savaging my mind. And it comes to me, and I do something I haven’t done for years. I bow my head and I pray. I pray for a miracle. I pray that I die quickly.

TWENTY-THREE

Parrots wake me, screeching nearby.

My prayers went unanswered. I’m still alive.

The realisation that I’ve survived the night brings no relief. Just pain and hunger and a searing thirst. My legs ache as if they’re encased in concrete and the cold night has compressed the mud around my chest so much that it’s painfully difficult to breathe.

Nothing else has changed. I’m still going to die. All that’s happened is the list of possibilities of how the jungle will kill me has grown, and now I can add a slow, lingering death from dehydration or starvation to the list.

By mid-morning I’ve scraped up all the moss within reach and sucked every last trace of moisture from it. But it’s nowhere near enough to quench my thirst and the morning passes in a haze of pain and hopelessness. And hunger. And thirst. Always thirst. Agonising, brain-shrivelling thirst, until sometime around noon when, with the blazing sun directly above me, and my head feeling as if it is about to burst into flame, it becomes clear what I can do. I can let go. I can simply let go and slip beneath the surface where it’s cool and safe and the sun and the insects can’t reach me. I can beat the jungle after all. I can win.

I raise my arms above my head and wriggle my upper body but I don’t move. Not an inch. The same sun that’s frying my brain has baked the mud solid and I’m held fast. I’m going nowhere. The jungle won’t even let me kill myself.

And with this thought something crumbles in my mind. Some sort of mental barrier, and the memories come flooding back. I remember the crash. I remember the plane plunging and pitching, and the pounding rain. I remember the spluttering engine and the streaks of flaming oil lashing my window. I remember being frozen in my seat, too terrified to move while the plane juddered and lurched and luggage ricocheted around the cabin. I remember the force of the dive pinning me to the back of my chair and my fingers digging into the seat rests. I remember Dad yelling at me to buckle my seat belt and put my life jacket on. I remember using my life jacket as a pillow while I slept, and how it flew out of reach to the back of the plane. I remember unbuckling my seat belt earlier, to be more comfortable while I slept, even though I promised Dad I wouldn’t.

I remember Dad undoing his seat belt and clawing his way across to me, bracing himself against the door handle while he buckled mine. I remember the look in his eyes as he took off his own life jacket and thrust it over my head. I remember grabbing handfuls of his shirt and clutching him tight and not letting him return to his own seat as the engine coughed and died and the plane plummeted. I remember the shirt ripping and Dad flying away from me as we slammed into the water.

The shock of recall is overwhelming. The brutal truth about what happened to Dad. The sickening realisation that he’s dead. And it’s my fault.

I thought the pain was bad before, when the helicopter left, but this is worse, much worse. It feels as if my ribs have been snapped in two and the jagged ends are being screwed into my heart. My chest heaves against the unyielding clay and I wheeze and blink uncontrollably, but I do not cry. I cannot. My body has no moisture left to spare for tears.

I have never felt such despair. Such misery. I want the jungle to finish me. I don’t care how. I just want the pain to end. I raise my head and in a hoarse voice I scream, ‘Do it. Do it now!’ But I know I’m wasting my time. I’m condemned. Subject to the mercy of the jungle, and the jungle has no mercy. It wants me to suffer some more. To know I’m powerless, and I have been all along. It wants me to know it can snuff out my insignificant life any time it likes, just like I squash a mosquito, or crush the ticks burrowing into my skin.

The scream has exhausted me, and it feels like my lungs have ruptured from the effort. I don’t even have enough strength left to hold my head up and it drops to my chest. So I do the one thing I still have control over. The one thing the jungle can’t take away from me. The only thing that makes any sense.

I close my eyes and I pray. But this time I don’t pray for death or for the pain to end.

I pray for the impossible instead. I pray that Dad is alive. I pray he makes it home to Mum.

And with thoughts of Mum now filling my head I remember the last time we spoke, and every word she said. I remember the look in her eyes when she made me promise I would be careful, and do what Dad told me to, and come home safe. And I promised.

I pummel the ground, and try to scream, but my throat is too dry, my tongue too swollen. I do not want to die. I want to live! I so badly want to live. I have to. I have to make it back to Mum. I have to keep my promise.

It starts to rain.

Lightly at fi

rst, pattering through the trees. I throw my head back and stretch my mouth wide, and frantically gulp the cold water. The shower quickly becomes a deluge, drumming on my head and shoulders and pooling around me. Lightning flares through the canopy and I can see the clearing has been transformed into a shallow pool, and even in my deranged state I realise the water level will soon rise above my head and I will drown, or it will liquefy the clay encasing me and I will slip beneath the surface and choke to death as my lungs fill with rancid mud. And my body will never be found. And as the rain falls hard and heavy, and thunder quakes the air I make another promise. I make a vow on my own life that if I can just escape this watery tomb I will find a way to get out of the jungle and make it home to Mum. I swear I won’t leave her alone.

Thrusting my hands through the water, I press down into the sludge, trying to lever my legs out, but my body still won’t budge and the effort sends a stab of pain shooting up my spine.

The water level keeps rising fast and there’s so much rain hammering down and rebounding into my face that every breath I take seems more liquid than air. I never imagined the sky could hold so much water. Or release it with such force.

But the battering seems to help. It flushes and revives my brain. From a distant corner of my mind I hear a faint voice telling me to calm down, to control my emotions and concentrate. And I know the voice. I know it’s Dad! ‘Take a deep breath and calm down,’ he says again, in his measured, steady voice. ‘You can do this, you just have to focus and find a way.’ And I so badly want to believe him, to believe he’s right, so I squint through the driving rain for any sliver of hope, anything that might be of help. Another bolt of lightning splits the darkness and I can see the tip of my bone club sticking up through the water, and I have an idea.

I grab the bone and ram its jagged end into the spot where the reeds were, and pull. The bone tilts and pops free almost immediately and I let out a cry of anguish before trying again. This time the bone stays in place, but my wet hands slip free and I scream. I try for a third time, cautiously pulling on the bone, checking the resistance. It holds firm so I clamp both hands tight around the shaft and pull. Blood pumps from the cuts on my palms and a searing pain shoots up my spine, and I let go and howl again, gutted by my failure. It’s no good. I can’t do this!

But I have to. So I wrench the bone free and drive it back into the mud, deeper this time. I feel it snag and catch, and I pull, and I think I feel my legs move. Leaning as far forward as I can I pull again, and this time I’m sure I feel a slight give around my waist.

Clenching my shoulders I pull again. Another stab of pain shoots up my spine and it takes all my willpower not to let go, but I know if I do I’m finished. I will sink further into the mud and the bone will be out of my reach.

With my hands still wrapped tightly around the bone, I take a deep breath and press my face into the water, burying my nose in the mud. And I pull. With strength I never knew I had, I pull. With blood pouring from my hands and my lungs screaming for air, I pull. With the muscles in my arms threatening to tear in two and my shoulders feeling like they will pop out of their sockets, I pull. With my spine stretched to breaking point and the blackness of the water seeping into my brain, I pull. With a fire blazing in my chest, I pull.

My legs move, and I rise just enough to be able to lift my face clear of the water and breathe again. Now I can scream while I pull. So I do. I scream louder than I ever have before. I scream abuse at the jungle, and the storm, and the mud, and my puny body.

I scream with all the rage and volume I can muster. The sound comes from deep within me, from my core, rising through my blazing chest and erupting from my mouth in a howl of defiance. It’s a sound I didn’t know I was capable of producing. A sound like no sound I’ve ever made before. I will not die here, not like this. I refuse to! To die means breaking another promise and leaving Mum alone. It means giving up and letting Dad down, and I won’t do that. Not again.

So I pull. I pull and I scream.

And with a sudden lurch my waist rises a few centimetres from the sinkhole. I pull again, now able to gain some leverage by digging my elbows into the mud below the water and pushing down, and another few centimetres of my body slides clear.

I don’t know how many times I repeat the same excruciating action, or how long it takes me to reclaim my body from the pit, but centimetre by impossible centimetre, that’s what I do. Snorting and spluttering. Straining every fibre and sinew until my feet slide from the hole and I can drag my leaden legs clear, and slither out of that cold muddy grave. I grab the first tree I reach, wrap my arms around its trunk and grip it as tightly as I can in case the mud rises up to swallow me.

The rain eases, gently massaging my body and washing the mud away. Then it stops. My racing heart slows to normal speed. I let go of the tree and I stand. Blood flows back into my legs, inflamed with pins and needles, and I accept the pain. I welcome it. It means I’m alive. It means I didn’t give up. I can only manage two faltering steps before my legs buckle and I collapse. But I will not stay down. I don’t have to. I’m stronger than this.

I stand. I stand because I know I can. I stand because I have to.

Bone club in hand, I take a last look at the still, moonlit pool behind me. Then I spit into the black water and turn and walk away.

I have a promise to keep.

PART THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

The helicopter isn’t coming back.

However much I don’t want to believe it, I know it’s true, and the longer I stay here, the greater the chances are that something is going to get me – animal, insect, disease, injury or starvation, whatever. It’s raining more often as well, making it harder to keep the fire alight. But at least the storm that almost drowned me in the mud pit also dumped loads of wood on the sandspit, so I don’t have to spend so much time searching for fuel. And with any luck somewhere amongst the driftwood I will find the material I need to complete my task – timbers to build a raft.

Walking out is not an option. There are too many snakes and other deadly things in the jungle, and there are no trails to follow. As soon as I lost sight of the river I wouldn’t know which direction to head in. Even if I did have a vague idea, I don’t have a compass, not that I know how to use one anyway, and since the sun isn’t visible through the dense canopy, I couldn’t use it to navigate by either, so there would be nothing to prevent me from going round in circles. And I won’t risk ending up deep in the jungle without a source of drinking water. No. Heading into the jungle is simply too dangerous. My only possible escape route is the river.

Even with its piranhas, caimans and rapids, the river is still the least worst of two crap options. Anyway, I don’t have a choice. No one’s coming to get me and if I stay here I will die. I got cocky, thinking I could beat the jungle. Lazy too, neglecting the fire and my HELP sign. I realise that now, and once the relief of escaping from the pit had faded, I spent most of yesterday and last night feeling massively depressed and pissed off with myself. But I’ve finally got it through my thick head that it’s a complete waste of time beating myself up over things I can no longer do anything about. I have to stay positive and tell myself it’s not too late. I have to believe that if I work harder than I ever have before and I’m not careless, or too hasty, and stay focused on just one thing – building a raft – then I will make it out of here. There can be no more delays or diversions. No more time squandered on improving the camp site. No more mistakes. From this moment on, everything I do has to be done with only one aim in sight – to get out of the jungle, and back home to Mum.

I pick up my rod and the three piranhas I’ve caught and take another hopeful look at Otter Rock. There’s been no sign of Galaxy or his mother since my return the night before last. I guess they must have moved on, probably to reach higher ground before the rainy season arrives. Maybe. I’m trying hard not to think about them too much, but the truth is I desperately miss their company, Galaxy’s especially, even i

f a small part of me is secretly relieved he’s not here. I can’t afford any distractions and I’m not looking forward to saying goodbye. So I try to console myself with the knowledge that, however much I miss him, at least this is Galaxy’s home and he’s with his mum. Now it’s time for me to go to home and be with mine.

TWENTY-FIVE

The next two days pass in a sweaty grind of driftwood sorting and hauling, fishing and foraging for provisions. I’m permanently exhausted and filthy, apart from when it rains. My bed stays unchanged and mouldy. I don’t bathe. My teeth are unbrushed and furry. I don’t take a break at midday, and although I’m hungry all the time I barely pause to eat until after the sun’s gone down. I’ve lost so much weight even my pants are too big for me now and the elastic’s shot anyway, so I go naked all the time – apart from occasionally wearing my trainers, when I need their protection from ants and thorns.

While I don’t bother with the smoke signals any more I do spend some time coaxing the fire back to life in the evenings, when it’s not raining, to cook and eat as many fish as I can. All this physical work gives me an insatiable appetite, and I know I need to consume as much protein as possible to build my strength for the raft trip. And after finding more large paw prints by the stream I really don’t want to be without the light and security of my fire. But despite the exhaustion, the rain and Galaxy’s absence, overall I’m feeling pretty positive. Doing something constructive instead of waiting for something to happen feels good. It feels like I’m in control.

After many hours of boring sorting, I have the material I need to build a raft – three small trunks and two thick branches, and a pile of bamboo poles to provide extra buoyancy. Hauling them all to a launch site on the riverbank has taken every ounce of strength I possess and most of the skin from my knuckles. If Mum had heard the swear words spewing out of me over the last couple of days I’d be grounded for the rest of my life.

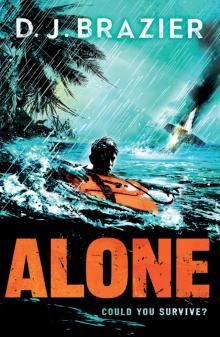

Alone

Alone